Among these were a series of gloomy city scenes by Pryde, generally focusing on an archway as an overriding feature.

|

| The Slum, 1916 Image found here: https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/the-slum-142570 |

|

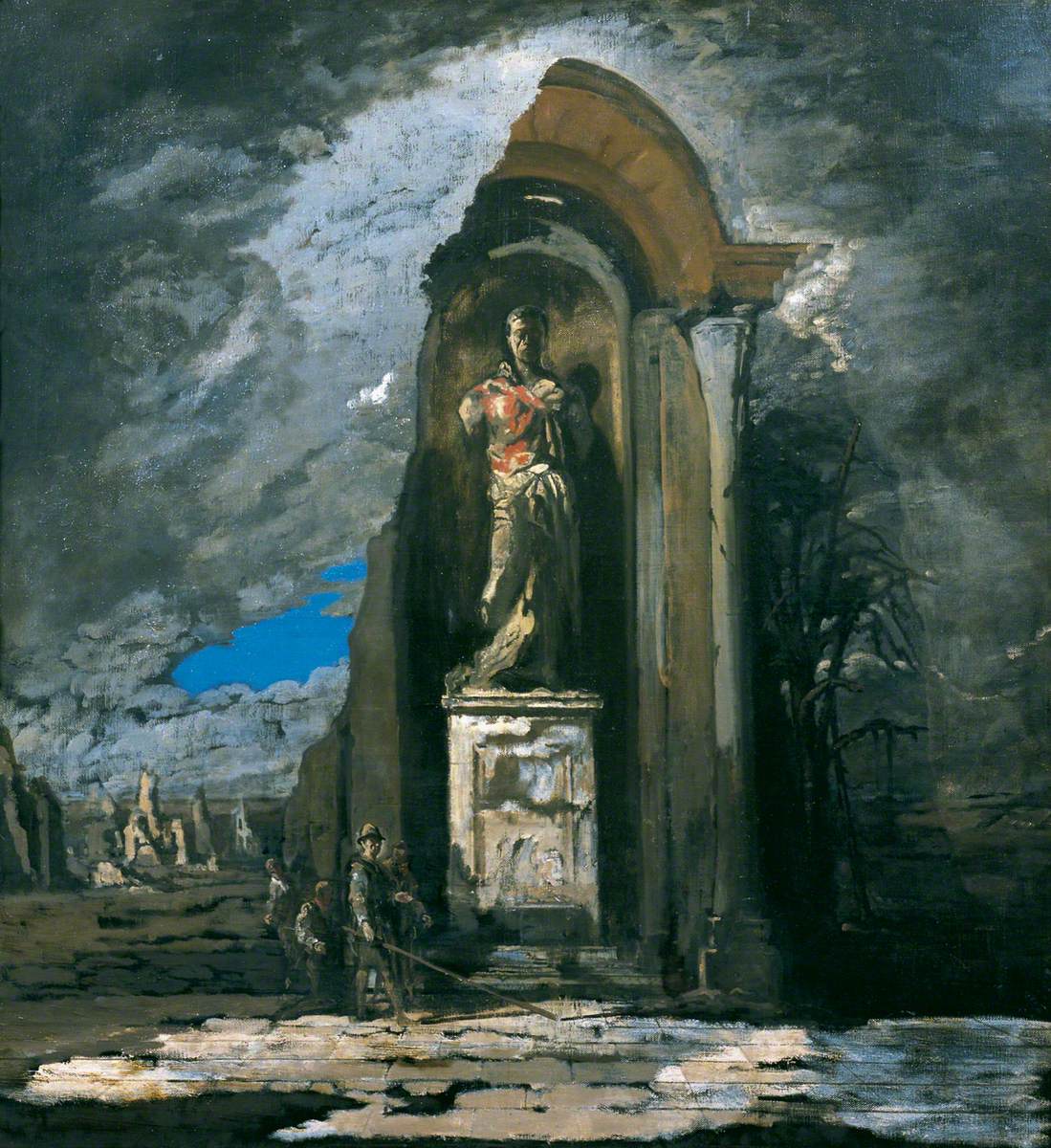

| The Monument You'd never guess these were made around the First World War, would you? Image found here: https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/the-monument-29078 |

|

| I don't want to give the impression these all involved arches. I think this one involved Venice. |

***

That might have been where the post finished, but no. My reading of late has taken in The Old Ways by Robert Macfarlene, as well as Patrick Stuart's Silent Titans (which I might write a dedicated response to later on). Either way, my mind has been homing in on landscapes.

Does the the corner of tabletop roleplaying I am interested in have much scope for the large, the slow - the geological? Hexcrawls abound, but they have a tendency to seem a little unnatural - oddly curated. Perhaps it is the GM's jobs to smooth the discrete hexes into the flow of a realistic landscape. Enclosed spaces: Dungeons, Cities, Mazes, Caves - these are the places in which the most impressive work has been done. Even if the scale is inflated it is still an enclosed, finite space. Puzzle-box environments, full of mechanisms.

Could this be done in a natural (or largely natural environment)? The Gardens of Ynn are rather too managed (or, formerly managed) for this to take place, and the Wir-Heal of Silent Titans has been so comprehensively fractured on the dimensional level I'm not sure either count. The video game Fallout: New Vegas had Zion National Park, with its maze of canyons and possibilities for verticality, which comes pretty close to this.

However, thinking of the sweep of the landscape one encounters on walks: in which each spur seems to promise the tip of the headland, where long empty skies change the system of thought, where the terrain under foot changes your whole mode of walking (try going from a sandy beach to a pebble beach). The scale of landscapes seen from above in Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings, bare and vast. T. E. Lawrence, in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, writes about how dramatic a change of rock was to campaigning in the desert, because of what it meant for vehicles or beasts of burden. Reading about this made it seem as dramatic as a minefield or an obstacle like an enemy bunker, because of the hostility of the desert (Lawrence is good when writing about rocks).

Perhaps the small-party-of-adventurers is the wrong unit for a game to talk about landscapes. Even mounted, they don't necessarily move quickly enough to take it in. Joseph Manola's Against the Wicked City is good about discussing the sweep of Central Asia, but passes over much of the countryside proper (see the comments in that last link). This is hardly blameworthy; Manola wishes to make Against the Wicked City, not Steppe Simulator Five.

Perhaps the place to look is to vehicle combat as a central gameplay feature. Mad Max is the touchstone - not in terms of the internal combustion engine, the post-apocalyptic or Australia, but in terms of speed, the importance of relative position, the possibilities of open space, the consequences of terrain (not that you can't traverse something, but what it will do to you as you traverse it).

This may merit further research, as well as mooting a series of simple settings suitable for this kind of combat.