This is the point where I talk about William Morris.

|

| Pictured. |

Of course, one would most likely call neither Morris nor Tolkien an Anarcho-Primitivist. Both make a place for the work of the smith and the machine. The crafted sword of Aragorn may fight off numerous manufactured orc blades - something which has echoed in named weapons throughout post-Tolkien fantasy, even into the often deconstructionist A Song of Ice and Fire. Such swords provide material for the cynical or satiric fantasist; I paraphrase Tom Holt in referring to a King suffering a blow from "not a battle-axe with runes all over the blade- just something run up by the local blacksmith." Morris seems willing to have embraced elements of mechanisation in the production of his textiles, even as he criticised the omnipresence of industry and its effects.

Dwarves are not the only craftsmen in Tolkien, of course, but they have the most association as a race with that notion - from their creation by the Valar smith Aule, to their lives within a crafted environment in the mines. Such notions go back to the Poetic Edda, but this deserves spelling out.

All this goes doubly so for Post-Tolkien work, which can ramp this up quite considerably (see, for instance, the black powder, gyrocopters, steam tanks, and blimps of the Warhammer and Warcraft franchises).

|

| A Warhammer Fantasy Dwarf Gyrocopter minature. From 8th Edition |

This might have an angle of the Victorian socialism of Morris, but it would be a mistake to have non-human society when worldbuilding imitate precisely the ways of any given political system or culture from human history. Moreover, to quote from Tolkien's friend and colleague C.S. Lewis in Mere Christianity, "There will be no manufacture of silly luxuries and then of sillier advertisements to persuade us us to buy them*....We should feel that its economic life was very socialistic and, in that sense, 'advanced' but that its family life and its code of manners were very old-fashioned - perhaps even ceremonious and aristocratic." This is not perhaps an entirely pertinent quote in itself, but elements of it might reflect upon an optimistic view of this Arts and Crafts Dwarven polity.

Pivoting on this awkward quote, I should like to suggest that these dwarves already, after a fashion exist: in the work of C.S.Lewis. Not, as might be obvious, the dwarves of Narnia, but some of the denizens of Malacandra in Out of the Silent Planet from The Cosmic Trilogy. I speak of the Pfiflitriggi.

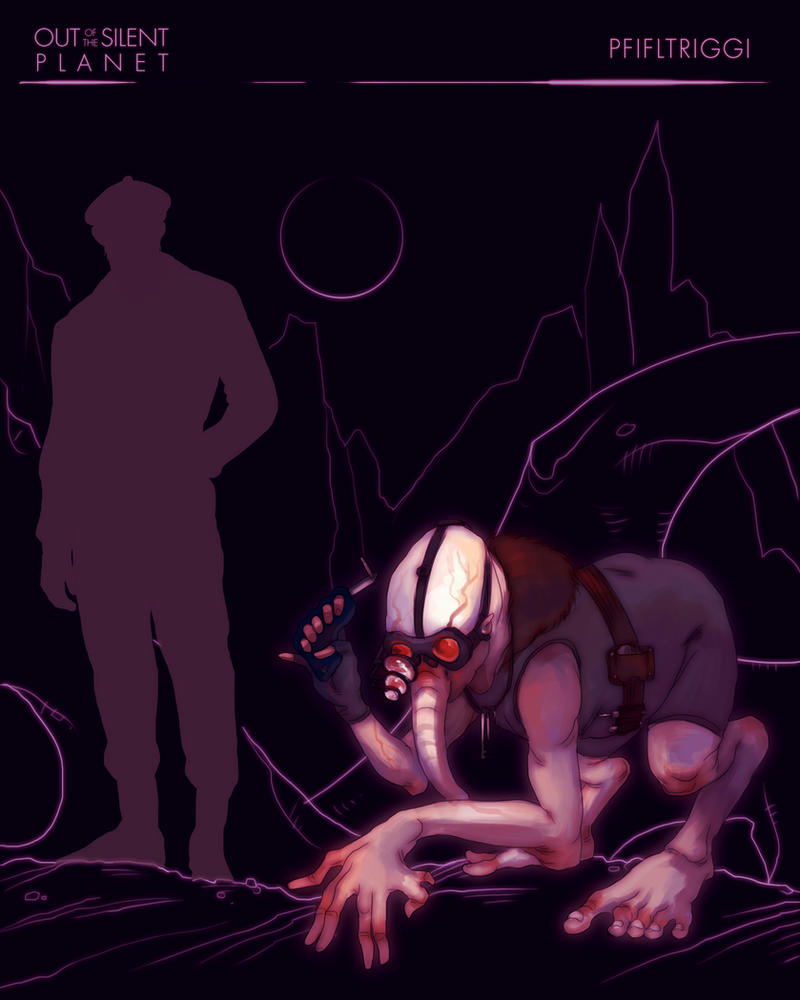

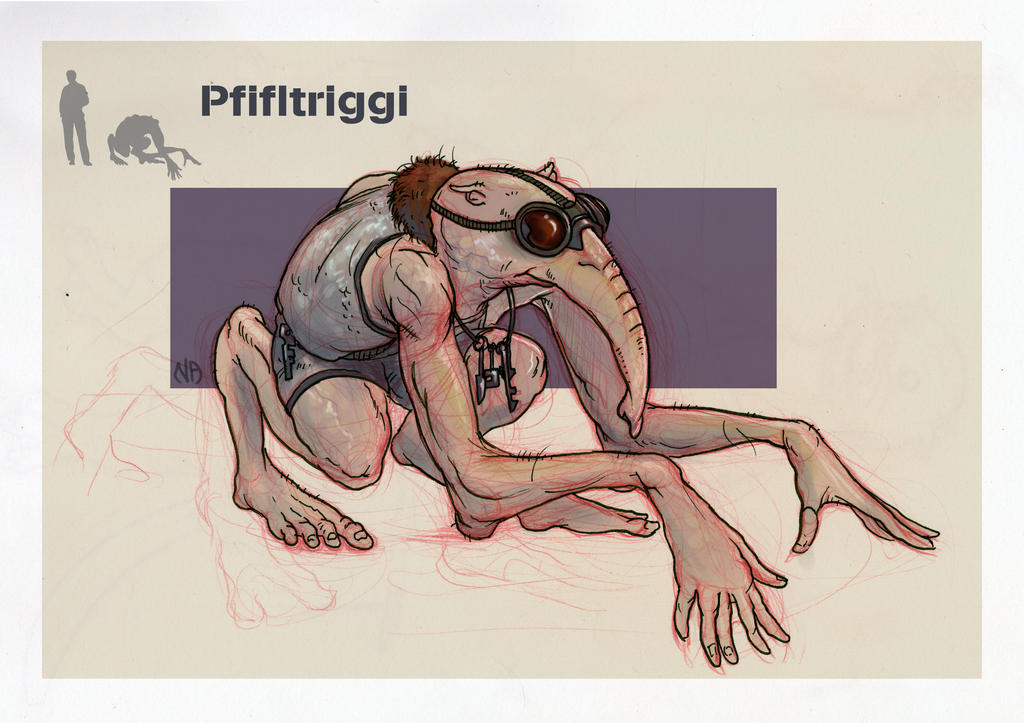

How to describe them? The face is "long and pointed, like a shrew's, yellow and shabby-looking, and so low in the forehead that....much more insectlike or reptilian...Its build was distinctly like that of a frog...that part of its forelimbs on which it was supported was in human terms, rather an elbow than a hand. It was broad and padded and clearly made to be walked upon, but upwards from it, at an angle of forty-five degrees, went the true forearms - thin, strong forearms, ending in enormous, sensitive many-fingered hands." About their bodies, they carry a number of small instruments. One that the protagonist, Dr Ransom, meets is dressed "in some bright scaly substance which appeared richly decorated...It had folds of furry clothing about its throat...dark bulging goggles...Rings and chains of a bright metal ...adorned its limbs and neck."

|

| By Nathan J. Anderson. |

The Pfiflitriggi are suited to be craftsmen; the one met in Out of the Silent Planet is a sculptor. When asked about their position with the other races of Malacandra, he says "No one learns the speech of my people, for what we have to say is said in stone and sun's blood and stars' milk." Their homes are in "The true forests, the green shadows, the deep mines," with "houses with a hundred pillars, one of sun's blood ,and the next of stars' milk all the way...and all the world painted on the walls."

These mines are worked by all, though "each digs for himself the thing he wants to work"; if a pfifltrigg does not work the mines, how is he to "understand working in sun's blood unless he went into the home of sun's blood himself and knew one kind from another and lived with it for days out of the light of the sky." There are hints of matriarchy - confirmed in Lewis's Postscript, along with the fact that they are short-lived among the races of Malacandra and oviparous. They bear names such as Kanakaberaka, Kalakaperi, Parakataru and Tafalakeruf. Such humour as they possess is said to be sharp and excel in abuse.

This is not perhaps very typically Dwarven. But the crafting and mining - and the semi-Utopian air in which it occurs - fit in very nicely with the 'Morrisian Dwarf', if such a thing can be. However, I believe that the humble pfifltrigg deserves a chance at adventure on the tabletop. Therefore, I propose to create a homebrew class for one for The Fifty-Two Pages.

THE PFIFLTRIGG

HP - d6+1+ CON +/-.

Attack Modifiers - +1 Melee/+1 Missile.

Mind Save 7 + WIS +/-

Speed Save 9 + DEX+/- [They are shown to jump quite far]

Body Save 5 + CON +/-

Knowledge Notice Detail Hear Noise Handiwork Stealth Athletics

[XX] [X] [X] [X][X] [ ] [X]

Starts with Background Words: Underground, Language: Old Solar and Two Pfifltriggi Tools (see below).

Level Advancement: +1 Melee/ +1 Missile every Fourth Level

+1 to all Saves every Odd Level

+1 Pfifltriggi Tool every Level (see below)

A Pfifltrigg may carry a great number of tools that may perform some physical function similar to Energy/Creation/Change spells or an otherwise bulky item of equipment. These have the same limitations as such spells (only so much fireball juice in the fireball machine). They gain such items once per level and must manufacture them personally, providing time and money for raw materials, parts and testing.

|

| By Nathan J. Anderson. He plays a mean harpsichord. |

*There seems something curiously resonant with the 'murderhobo' stereotype about this: either a piece of jewellery is enchanted, and useful; and thus worth keeping - or it is treasure, to be sold when the adventurer reaches the nearest large town. It would be interesting to see what would happen it was made clear that an amulet of strength (or what have you) was terribly beautiful, but mechanically inferior next to its counterpart.