A rousing tale of swordplay and sorcery, an appealing love story and a shrewd and subtle commentary on problems of politics, morals, and philosophy, all at the same time. Laid in an imaginary world, in a setting resembling medieval Scandanavia, it tells of the swashbuckling adventures of young Airar Alvarson...The story is full of action, colour, conflict and intellectual conversation, peopled by such vivid characters as the genially sinister old Doctor Meliboë the enchanter and the rough, passionate soldier-girl, Evadne. It will not only grip your attention while you read it but also leave you with so much food for thought afterwards that you will presently want to go back and re-read it.

L. Sprague de Camp, as quoted in the Gollancz Fantasy Masterworks edition (pictured below).

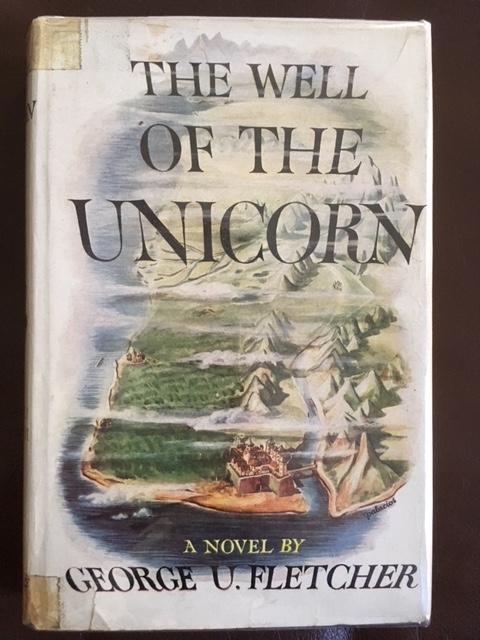

Let us establish this first: The Well of the Unicorn is a novel by Fletcher Pratt, first published in 1948 by William Sloane Associates under the name of George U. Fletcher (see cover of first edition, below). Fletcher Pratt (1897-1956) was, variously, a librarian, translator, and reporter - as well as an author. He wrote both a string of military histories, as well as collaborating with L. Sprague de Camp on The Incompleat Enchanter.

|

| The first edition of The Well of the Unicorn. The landscape is a stylised Dalarna. Photograph taken from Abe Books. |

The Well of the Unicorn he wrote alone, or almost alone. An element of its setting is taken from a short play by Lord Dunsany, King Argimenes and the Unknown Warrior (this play may be found on Project Gutenberg). It is set in an unnamed continent and deals with the division between the Dalecarles and the Vulkings for mastery of Dalarna. The two nations are of roughly similar types, but the Dalecarles were conquered by the heathen Dzik for a time, whereas the Vulkings were not. The rule of Argimenes expanded Dalarna into an empire ('The Empire') by marriage with an overseas Princess of the southern nation, Stassia, and the bringing of the yet more southerly Twelve Cities into the imperial fold.

This latter was accomplished by the titular Well of the Unicorn - the Well of Peace, the World's Wonder. The well, it seems, will grant peace (if not virtue, or freedom, or other boons) to a king's reign. The reader slows learns about it by several 'Tales of the Well' embedded as stories within the narrative - but Airar Alvarson is not on a quest to find it, or to protect it from the Dark Lord.

A Church is mentioned - apparently on the Christian model, but without any great discussion of its creed. Magic comes under its ban; magic is not common, but can be fairly readily learnt. Even if wizards and warlocks are few, the notion that magic could be employed is ever present and the Well acts as a pervasive religious-magic influence on the setting. Airar Alvarson certainly has a knack for it.

So, to the plot. Airar Alvarson, a Dalecarle of a good if impoverished family is evicted from the family farm. By contact with the enchanter Doctor Meliboë he is drawn into a conspiracy - the Iron Ring - against the rule of Count Vulk, who deals with the Dalecarles ill. Thus begins a tale, that if dealt with reductively may seem familiar: A young, gifted man is thrust out into the world to fight tyranny as part of a rebellion; he wages war on several different fronts with bands of heroic irregulars and characterful mercenaries against a harsh, established, featureless military and falls in love.

Well, this does have connections with previous musings on the place of a military in the products of popular culture. L. Sprague de Camp, from a review in Astounding Science Fiction Vol, 41 No. 4 describes it as being about 'the philosophy of government: how can men be organized to fight for their freedom without irretrievably losing that freedom in the process.'. That's not wrong. But aside from noting The Well's place as pre-Tolkien fantasy, I'd like to counter that reductive summary above.

Firstly, Airar Alvarson is a callow adolescent rudely awakened by his eviction. He is rarely in a state outside of war or peril for much of the book. Doctor Meliboë* - whose introductory chapter has something of TH White's Merlin about it, albeit rather more sinister - is more Svengali than Merlin. Airar has no steady mentor, despite a stable youth (his father is alive, if elsewhere and linked to the Vulking regime). He becomes rapidly surrounded by the conspirators of the Iron Ring and mercenaries of the Twelve Cities. Even if he is capable of holding his own, those around him constantly have their own agendas. And Airar is enjoying the fruits of freedom, status and power - which leads to romantic or physical entanglements. His grappling with the latter causes no end of internal wrangling and argument.

Secondly, I would note that Fletcher Pratt's own work on military history has clearly paid off. The necessities of campaigning - of shelter and fodder, of forced marches and rough terrain, of keeping the peace between proud quarrelling men in the midst of many weapons - are very real. The accounts of battles and siege engines may be a little over-detailled for some tastes, but they can be arresting.

|

| The cover of the Fantasy Masterworks edition. I do not recall a scene quite as Gothic, but some of the magic in The Well has something of this tone. |

A note on tone and style: the work is scattered with archaisms. Some reviewers associate this with E.R. Eddison, though The Well is far less developed in it's unique style than The Worm Ouroboros or Mistress of Mistresses. It can be an awkward style to read, but I got used to it (not everyone does). When reading it, my mind went to Walter Scott rather than anything else. Despite the violence of the book and the scattering of fade-to-black sex scenes, the Iron Ring still identify themselves by whistling a few verse of a song; trumpets still go 'Tira-Lira'; a nobleman urges on his troops by asking if they were 'suckled by rabbits'.** Perhaps we can see this as an outlier of the Walter Scott Fictional Universe that looks ahead to 1960s-70s historical/fantasy works; it certainly bypasses Tolkien.

The Well of the Unicorn is at least interesting to talk about - who knows if the above has actually sold it to you as an appealing prospect. It's low magic setting may be arresting. I would argue, however, that it gives a fascinating example of 'clerical magic' in the Well. This isn't the parish priest giving you 1d6+1 hit points or Holy Water = Acid for Vampires, but is a pervasive social and cultural feature, which while it definitely works, offers mixed results. More to the point, it has deliberately spiritual (or possibly 'character-effecting') qualities to it rather than being a simple tool (Mother Atsilva healed your gangrenous leg wound; now you can go right back to plundering dungeons and killing orcs!). I don't know how one would go about modelling it, but it may be worth a thought.

*Micheal Moorcock is apparently appreciative of The Well, but I have not seen any explicit links between the names Meliboë and Melniboné.

**This just makes me want a big-budget Game of Thrones-esque TV series, but all the dialogue is relatively tame semi-Shakespearean material of this kind. All the blood and nudity you could wish for, but nary a four-letter word in sight. And a selection of actors that have to taken this very seriously indeed.