Forget the religious artefact at the centre of the film; think of many of the action scenes. Raiders of the Lost Ark (RotLA) has that business with the twin-rotored aeroplane and the chase scene with the convoy (many separate vehicles, one figurative machine). The Last Crusade (TLC) has a many-turreted tank with restricted vision - with a convoy behind it. In both cases, one man (on a horse) wreaks havoc on it.

[Of course, there are two kinds of machine in these films. The modern military device and the ancient dungeon full of traps. Both are dangerous - might we say that only one is malevolent?]

This is partly because it provides amble opportunity for peril and derring-do. But the repetition of this kind of scene gives (if you will) a little license to unpick this.

I would not think of this as technophobic, or luddite. But our hero does not fight against the villain not as liberty-loving American to Nazi or archaeologist to soldier - but as man (and horse) against machine, the perpetual spanner in the works. Which could be construed as odd. The Indiana Jones films, even if they never portray the Second World War, constantly invoke it. Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (KotCS) even confirmed what I imagine everyone already conjectured: that Jones had continued to thwart Nazi occult ambitions in the Second World War - before Pearl Harbour, even.

Though, of course, we can never see this. Indiana Jones cannot take part in D-Day even if he is of the same spirit as D-Day. This would bind him too closely to a vast military machine. But just such machinery helped ensue Allied victory in the Second World War. Clearly, of course, Jones is not a druid or an ascetic. He buys tickets on aeroplanes, he carries a revolver. There is still a friction, when one begins to think on it. The stonewalling bureaucrats at the end of RotLA hint at this; the McCarthy era G-Men in KotCS confirm it. KotCS also gets to have the cake and eat it, by having a first Act with Soviet baddies dressed as American GIs. To say nothing of the horror of an American nuclear weapons test.

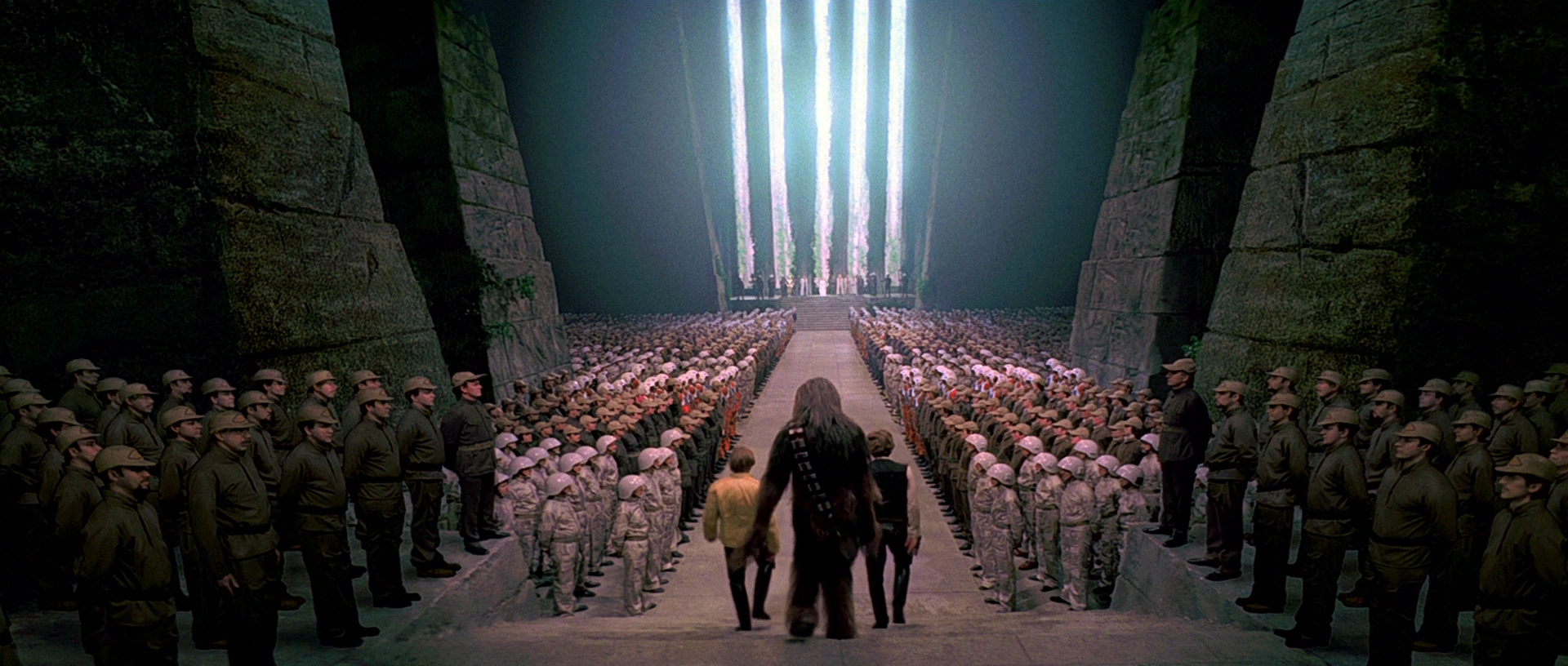

Star Wars - certainly the more recent films - suffers something similar. The Rebel Alliance is talked about in terms like the French Resistance - and it certainly is a resistance movement, against a vaster tyrannical force. But when we see it in Episode Four, it brings to mind the Royal Air Force in the Battle of Britain: unquestionably on the back foot, but still with the might of a World Power behind it. We see established chains of command, radio operators and ground crew, fighter wings, rank badges, call signs - all quite explicitly military and systematic rather than the ad hoc arrangements of a resistance. To say nothing of that orchestrated, disciplined medal ceremony at the end.

|

| Pictured: Rebellion. [From the 1977 motion picture Star Wars, Dir. George Lucas] |

I dare say there's some excellent in-universe explanation for all this. The parts of the puzzle still don't quite fit, or don't fit pleasingly.

(Incidentally, if you cannot guess the comparisons between the concept of a military machine and the Death Star, I have just made it. The arguing boardroom of generals with the Dr Strangelove table is a good touch. Further, Episode 4 ends with the inexperienced pilot in the unspecialised machine with the targeting computer off succeeding where the experienced bomber commander with the computer on fails.)

This doubles in later films. The explicitly distancing of the Resistance in Episodes Seven and Eight from the New Republic is odd; are we meant to understand by the finale of Episode Eight that a credible fighting force can be rebuilt from a platoon of soldiers onboard the Millennium Falcon? Allow me to raise the Battle of Britain comparison once more - the whole matter becomes a little risible, even if that last British platoon has Churchill, Monty, Douglas Bader, Orde Wingate, Dowding, Alan Turing, Barnes Wallis and Popski in its ranks. (The explicit condemnation of arms manufacturers should also be considered.)

[Am I complaining of a lack of realism in this tale of space wizards and funny robots? No, but, the verisimilitude of ground crews and radio operators and flight suits (rather than spandex) and so forth is part of the strength of this realised, lived-in world. I would say the same for troop numbers.]

So what is to come of all this? What are the reasons for the above phenomena? What conclusions can we draw?

It has been observed by critics before the strange distance between soldier and military in modern (frequently American or American influenced). Soldier good and sympathetic; military - especially staff officers - bad and unsympathetic. This is not simply, I should say, a party lines issue. One can imagine the heroic individualistic protagonist defying or breaking with his orders so that he may capture the villain - or summarily execute him. Indiana Jones and Star Wars have fuelled or continue to fuel this horror of organised hierarchical systems as much as Dirty Harry or Rambo, in their way.

What to blame? The Vietnam War would be a favourite candidate, but it cannot accept all the blame. The face of warfare itself has changed; the mass troop movements, conscription and industrial output of the World Wars are not to be seen. Not that the modern Western military does not face troubles of logistics - think of the Falklands Conflict, fought on the other side of the globe by Britain. But it does not need rifles by the thousand and tanks by the score to face terrorists. The squad comes into focus, not the regiment. This dovetails with the surrogate family narratives that seem to abound in adventure flicks these days - whatever the setting. But a regiment (or something regiment-like), however familial it might be in some respects, sits directly inside larger systems and is just too large. Trying to inject the former inside the latter doesn't sit correctly.

Yet the military machine - or any vast hierarchical system - has its uses. If those bits of the world most influenced by the films and narratives here discussed ever had to fight a war en masse, there would be some very odd dynamics at play within the stories that would then be told. We will not be saved by less than a dozen amiable, snarky 'badasses' with a deep interpersonal bond, but by vast numbers of people from a variety of backgrounds and with a variety of personalities who may not even get on terribly well. Neal Stephenson's The Diamond Age puts it thusly: “It is the hardest thing in the world to make educated Westerners pull together”. The internet may have changed that, but it enables all those pulling together to pull just as much as they wish to and in the precise way they wish to. This may not necessarily be objectionable to you, but it is something to consider.

Is there an antidote, for those than desire it? Tom Clancy novels, perhaps. But little on the big screen these days. Perhaps someone will make a 'military procedural'. But not yet. We Were Soldiers might be something to contemplate, though I can think of little that would be set in the contemporary. At any rate, I doubt there will be anything of the sort made in speculative fiction, no matter how many Star Wars spinoffs are made.

[If you want the tabletop take on it, go here and mine the archive for the follow-up posts.]

Have been eliminating the many tabs I have left open yet unread over the years - came across this post in the process - enjoyable and thoughtful, thank you for writing it.

ReplyDeleteThanks for saying so! I think this one's held up fairly well. Although if I had foreknowledge of Andor, perhaps I'd have modified that last paragraph.

Delete